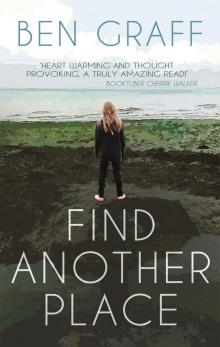

Find Another Place Read online

“Heart Warming and thought provoking a truly amazing read! I adored this book! I laughed, I cried, I nodded my head in agreement, as someone who has not only lost a parent, has a parent with MS and is a parent myself I could relate to this book on so many different levels and it will stay with me for years to come.”

Cherrie Walker – Booktuber.

“Family man Ben Graff knows that life is like a chess game, punctuated with triumphs and disasters and a constant search for the truth. He understands that the purpose of life must be to have a life of purpose and we are all but chess pieces in the magnificent game of life.

This is the brave and honest account of a man who lives his life as he plays his beloved chess. Always curious and intelligent, simple and yet complex. Graff drew me into his world of discovery from the first page and taught me that without hope you cannot start the day… A quite remarkable story.”

Carl Portman – Chess Behind Bars

“A well written, thoughtful family memoir, which anyone with a family can relate to.”

Kate Jones – Bookbag

Ben Graff was born in Aldershot in 1975.

He read law at Bristol University.

Find Another Place is his first book.

Find

Another Place

Ben Graff

Copyright © 2018 Ben Graff

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1789010 442

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For all of them

‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.’

L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between, 1953

‘Do not ask your children to strive for extraordinary lives. Such striving may seem admirable, but it is the way of foolishness. Help them instead to find the wonder and the marvel of an ordinary life. Show them the joy of tasting tomatoes, apples and pears. Show them how to cry when pets and people die. Show them the infinite pleasure in the touch of a hand. And make the ordinary come alive for them. The extraordinary will take care of itself.’

William Martin, The Parent’s Tao te Ching: Ancient Advice for Modern Parents, 1999

‘In my youth I was determined to become a writer. I tried to write stories about spies and criminals, a world of which I had no experience. Little did I realise that the family I have just described provided the material for any number of novels. By the time I did realise it, it was too late.’

Holmes Family History – As remembered by Martin Holmes, 2000

Dear Girls (special)

11/11/04

‘Just a few bits & pieces for you both. The velvet trousers will look adorable on you, Annabelle, & the pink outfit is for you, Madeleine. Give my love to Mum and Dad. Will be seeing you all at Xmas. Until then, kiss, kiss, kiss.’

Grandma Theresa

Contents

Foreword

Prologue – Our 9/11

Introduction to Martin’s Journal

Martin’s Journal – Meeting My Father

Waiting to be Ripped

2014 Part 1

Rigorously Pragmatic – 17 October 2014

Introduction to Four Seasons

Anna’s Letter –Yarmouth Car Ferry – 1975

Moving In – 1983

“We’ll Always Have Bognor” – 8 August 1988

2014 Part 2

Arrivals – 17 October 2014

Dad’s Work

Martin’s Journal – Schooldays

Playing Games – 1989-2014

All Our Christmases

Martin’s Journal – The Island at War

Chess Stories – Bobby Fischer Broke My Heart

Other Visits – Mountains and Rocking Horses

The Mouth of Hell, and Some Writers

Mary and Colin Graff – Letters

Disastrous English Lesson

‘A letter about things’

Diametrically Unopposed

Another Bash

Cars and Fred

All We Can Keep

Down In The Dumps

Tahiti Blue

Life Apart

Missing You

Worry So Much

You’re Super

Boats

Martin’s Journal – Holmes & Son

Helen

How Brave Helen Was

How Much More We Miss

Martin’s Journal – My Mother’s Family

One Time Abroad

Mary’s Journal – 1990

Golden Anniversary, and Other Football Stories

Martin’s Journal – Joan

Bristol – 1994

Martin’s Journal – Anna

Introduction to Aunty Noreen’s Diary

Noreen’s Diary – 1994

A Letter from Anna – 1994

Ghosts – 1995

Bognor – 2000

Martin’s Journal – Going Home – 2001

Mary’s Journal – 2003-2004

Chess Stories – Viktor and David – 2011

Find Another Place – August 2008

Dad’s Other Women

New Year

2014 Part 3

Endings

Maddie’s Memories – Sponge Cake and Wheeler Dealers

Francesca’s Memories – Christmas, Secret Sweets and Steep Hills

Annabelle’s Memories – Final Visit and More Sponge Cakes

The Kindest and Most Loving of Fathers

A Letter from Charmian

Afterword

Epilogue – Last Journey

Acknowledgements

Foreword

“Families are their stories,” said my grandfather Martin that late autumn day in 2001, as he placed a clear plastic folder containing his journal into my hands. His fingers felt cold on mine as they brushed briefly, the copper wrist bracelet he wore to help with his arthritis seeming to hang a little more loosely than before. The remaining hair on his head was the same natural black it had always been, the grey moustache neatly trimmed as ever, but he walked cautiously and weighed his words carefully, just as the writer he had always wanted to be might have done. He both was and was not quite the way I remembered him.

In the summer you would be able to hear the shouts of children playing at the sailing school across the creek, but they were long gone now, and other than the clank of the car ferry unloading, no sounds carried across the water. Over the years, I had spent many hours watching from the shingle of Fishbourne beach, and from the deck of family boats, as the ferries we

nt about their work. I had crossed this stretch of water at the beginning and end of family holidays, and listened to their low rumble in the quiet of the night, which was still just audible even from Martin’s house in Ryde.

We stood alone and it would be years before I saw that this moment too was also part of a story that could be re-told, made sense of or not, that had meant something once and might do so again. He had nodded proprietorially and told me that his story was complete and, if older and wiser, I might have seen something almost mystical, sacred even, in that moment, but I was not and I did not.

Now as I write this in 2017, his use of the word complete is what I think to most, and I can see that day again when we stood together outside the Fishbourne Inn on the Isle of Wight, with a breeze from the Solent gently blowing dying leaves off the trees and into the mud of the near-empty beer garden. There were no other patrons outside, nor any sign that there had been any. No beer that had been reduced to a layer of foam in lipstick-marked glasses, no cigarettes smouldering to nothing in abandoned ashtrays, no nearly empty plates yet to be removed by the waiting staff. After eating we had only come outside to get some air, and the meal had not been a complete success. He seemed distracted, perhaps thinking to what he was going to share, but it might have been that he was tired. I had lost at chess the previous night and kept drifting back to why I had pushed the pawn when playing the knight would have been so much better, unable to separate myself fully from the disappointment. He had fiddled nervously with the folder while we ate, but he did not mention it until now, when he handed me his story.

I did not ask whether he meant to say his journal was complete, or if he thought something more fundamental was drawing to a close. Perhaps I already knew. He had finished his writing and his life as good as, while at twenty-four my own was only just beginning to inch toward any form of definition, and my writing would not have overly employed whoever had printed and wrapped in plastic the copies of his journal.

I had met Katharine and she was pregnant, but we were closer to being married and further away from being parents than we thought. I was two years into a job that I did not much like but feared to leave, while Martin’s much more protracted career was long since over. Instead of the novelist he had wanted to be, he had spent his working life running shops that sold clothes, then shoes, finally musical instruments; I would later find that the other commercial ventures that were meant to give him a way out were described in his writing as disastrous and best forgotten. My own career had been mainly spent writing policy papers for a large organisation, which generally liked the way they were written, though the pieces were always wrong as somebody more senior either already had, or had not yet, decided what the answer was meant to be. In contrast, Martin’s journal was much more substantive, a last piece of work, a final project. As a matter of chronology, everything else he had done had led up to its creation.

If you don’t find a way to write things down it all gets lost in the end, or at least I think it does, he had said as we stood there. He told me that he had wanted to do this, to share the things about him that nobody else could know. His journal contained stories about him during the Second World War taking pot shots at planes from his bedroom window, an unrequited romance, boarding school in the 1920s, and difficulties with his father. It seemed that problems with fathers was a pattern that followed in our family just as regularly as white has the first move in a game of chess. This troubled me even on first reading, another potential warning sign, as being a father moved from being an aspiration, to something that had gone wrong, to finally a reality for me. I did not really understand what he had given me, or appreciate that his story was part of my own and that both of us were part of a tapestry of events that were larger and more complex still. I was subsequently to lose his neatly typed reflections and not think of them again for many years.

However, by 2016 much had been lost and much had changed. Many of those who had shaped the first part of my life were no longer alive and others had not so much taken their place in the family as created their own. Martin had been dead for fourteen years, my grandmother, his wife Anna, for twenty-two. My grandparents on my father’s side were gone too: Dave in the months before Martin, and Theresa in 2009. If there is a sense of following the natural order in losing grandparents, three of whom were in their eighties, the same does not apply for parents, even if theoretically you might think it should, particularly when both deaths are seen as untimely, both funerals peopled by many already older than either of them would ever get to be.

My mother Mary had died in 2008 at the age of sixty-one when I was thirty-two and my father Colin at sixty-eight when I was thirty-nine. One death shockingly sudden, the other expected, although I was surprised to hear it described as such. I always felt that the second half of my own life began on the day of her death; that things had started to turn and that while they would keep moving, they would not go back. The years that followed with my father after my mother’s death were not always easy, and then they too were gone. He was both more and less himself after her, and while we had more physical proximity during that time, it made our relationship more complicated, rather than closer.

But this is not all about deaths; there were new lives too. We had four children: Annabelle, Madeleine, Francesca and Gabriella. My brother Matthew and his wife Rachel had two, Reuben and Evie. I had become a parent and lost my parents. Everything was changing and, in amongst the business and the hustle, I wanted to pause to look not only backwards but also to the future. I wanted to remember some of the things that we did as children that had seemed to matter, while I still could. Remember, too, some of the things my parents had done. I missed them and wanted to talk to them again. I wanted to think about what it all meant for me, not just as the child I had been back then but also as the parent I am today.

I regretted that there were not obvious ways to reach them both afterwards. So much in my memory and in the memories of other people too, but nowhere else. Even the house they shared ultimately had to be sold. My regrets turned out to be only partially founded; there was more remaining than I thought, once I started to look for it. I found Martin’s journal again and it was to be the first of a number of discoveries. There were letters between my parents in a desk drawer from before their marriage, although in truth I did know about these. A handful, all carefully preserved in their original envelopes, even if on many the postmarks had faded. They were not in exact sequence but answered each other at a deeper level. They had been mainly posted from Bristol and the Isle of Wight by her, and from London by him, as she started out as a teacher and him a junior scientist. Finally they were stored in the two houses they were to own together in the course of their lives, the first in Aldershot, the second outside a small village in Herefordshire called Bosbury.

As we cleared out what had once been their house, I came across still more papers, in garaged boxes and the loft, in amongst broken bits of Hoovers, an old fireguard and several headboards. Some of the paper had a dusty smell from having been there for so long, but it was all dry and perfectly preserved. Fragments of other diaries, work records and poems, in amongst the more mundane insurance documents, old telephone bills and the various pointless pieces of print that accompany all of our lives, leading up to that final paperwork which is for others to complete on our behalf. We are all destined to get at least one certificate, my father once said.

From a vantage point in my own life I wanted to try and understand all of them better, when I was older than they were in some, if not all, of the moments that the following chapters explore. A chance for them to speak one last time, here on the page, and for me, perhaps, to speak for the first time.

As the family has evolved, births have followed deaths, the generations have intermixed and then separated out again, and the world has changed; while in some ways that matter less, it has stayed the same. For now, I remain as a witness to some of this, but only for now. Living and dying has

a force of its own, everything has a time, everything a season, the saying goes. There was a sense of this in my mother’s poems, which centre on Bosbury Church through the four seasons. A summer bride, an autumn harvest, all part of cycles that we can share in but will one day go on without us. I wanted them to live on in some way and I needed to find a different way to live myself.

I also wanted to write. If it was not for that, I might just have re-read Martin’s journal and my parents’ letters and the other miscellany and thought about all this and quietly worried about how best to parent and the generational challenges I had begun to notice. Yet my not writing was part of why I felt incomplete, and losing all of them had served only to accentuate my sense of loss. I did not want somebody in the future to say of me that I had wanted to write but did not; for even this memory to slip away, like the final ferry of the evening, the lights of which can be seen from the shore for a while, before all goes dark.

In the end I realised it did not have to be this way. The family had left so much paper for me, so many other memories and questions as their final gift, that sitting down to write was more joining a conversation than beginning one.

I had spent so many years trying to write, only for my efforts to go wrong, just as things often seemed to go wrong between me and my father; we would start out alright, only to get lost in a fog of misunderstanding that mutual good intentions did not always salvage. My first attempt at a novel was the dark and obscure Bleeding. I was twenty-two and it was about self-harm, my only experience of the subject a short story I had read. I did not believe in structure or other devices that might give the reader much of a clue as to what was happening (character names a sense of progression; a feel for time or season). I created a voice that was not my own, to tell a story that was not mine to tell. All cloaked in what I thought was literary language, but which rather than making Bleeding beautiful, made it as difficult to read as my father was, with far less reason for anyone to want to try.

Find Another Place

Find Another Place